"gifted kid burnout" & the ache of nostalgia

ascribing meaning to sadness & why we don't need to

…so I will!

I have a strange relationship with the term “gifted kid”. Put simply, I was never really one of them (but I desperately wanted to be).

Let me offer you a brief glimpse into what my younger self was like! In elementary school, academics were everything to me; I was exceedingly put together, wildly enthusiastic about the pursuit of knowledge, and generally regarded as a teacher’s pet. I spent every single recess reading and being very proud of how fast I could read and telling everyone just how fast I could read. I used to spend hours creating educational packets for my little sister to teach her kindergarten-level math and English. I sat at the adults’ table during get-togethers; I was lovingly bestowed the coveted title of “old soul” and touted as being wise beyond my years. I bought a massive pack of gel pens and annotated every piece of school reading in glittery purple ink. I committed to learning one new word a day to keep my brain sharp (it lasted about a week, but at least I still remember what “pusillanimous” means even though I will one hundred percent never use it colloquially or professionally). It feels cruel to say there was a level of arrogance there since I was literally eleven, so maybe pride is a better word — needless to say, it felt euphoric to know I was good at something. I wasn’t the prettiest, the kindest, or the most talented, but at least I didn’t feel like I was humiliating myself every time I walked into a classroom.

It’s crucial to note that I was not, however, gifted in the traditional sense. There was no particular program that branded me as an Exceptionally Brilliant Girl; I never took higher-level courses or skipped grades. I didn’t even feel that much smarter compared to anyone else, just a bit lonelier and more socially awkward. Actually, I kind of resented it; in order to uphold my image as a very serious, stoic, precocious girl, I had built up this level of guardedness that kept me feeling just a little bit detached from everyone else.

At the time, I knew I wasn’t all that special because I had a cousin roughly the same age who had already graduated high school — now that was a gifted kid. So I had manufactured a kind of a loose identity on being someone who was passionate about education, but there was never any kind of structural stability to my self-confidence. I always harbored this inkling it would come crashing down, and it did.

In high school, something shifted; I was no longer one of the smartest students in my grade — I was decidedly below average. I skipped several weeks of school due to unpredictable and enervating depressive episodes; I crammed for tests at four in the morning and did all my assignments at the very last minute. I fell out of love with academia, and my faith in my intellectual ability dwindled to almost nothing. I would cry during tests and hand them in with scribbled apology notes on the bottom; for one particularly difficult final, I turned in an entirely blank packet and didn’t even flinch at the idea of failing the class. Many times, I tried to convince myself that I hadn’t lost any of my intelligence, that it was just buried somewhere under a layer of hurt and worry — but it wouldn’t have made a difference either way. I felt dumb1, and it was the worst thing in the world (until it wasn’t).

Eventually, your brain adapts to that sort of thing; I got used to asking for extensions on assignments, I retook tests that I’d completely bombed, and I began to devalue academic achievement and intelligence in favor of promoting self-care and day-to-day survival tips. Keeping myself going became more important to me; I gradually and inadvertently distanced myself from that overachieving, hyper-anxious little kid until it felt like the two of us were complete strangers. It was a little painful and pretty embarrassing to admit to myself that I truly believed I peaked in fifth grade, but eventually, I swallowed it and the world went on.2 That’s what saved me, the humility. You’re not a prodigy, and that’s okay! You never had to be. Everyone’s just happy you’re here.

Someone might look at this story and try to reassure me — “No, you were a gifted kid! That was gifted kid burnout! You’ve just described it!” First of all, I don’t really care anymore, which is freeing! Second of all, I don’t think so. I do think I was a regular kid, albeit a somewhat passionate one, who just…grew up. I was forced to reckon with the natural obstacles of life and the expected consequences of mental illness, and it made me realize that things aren’t so easy anymore. That’s just the pain of emerging from childhood; it’s perfectly normal!

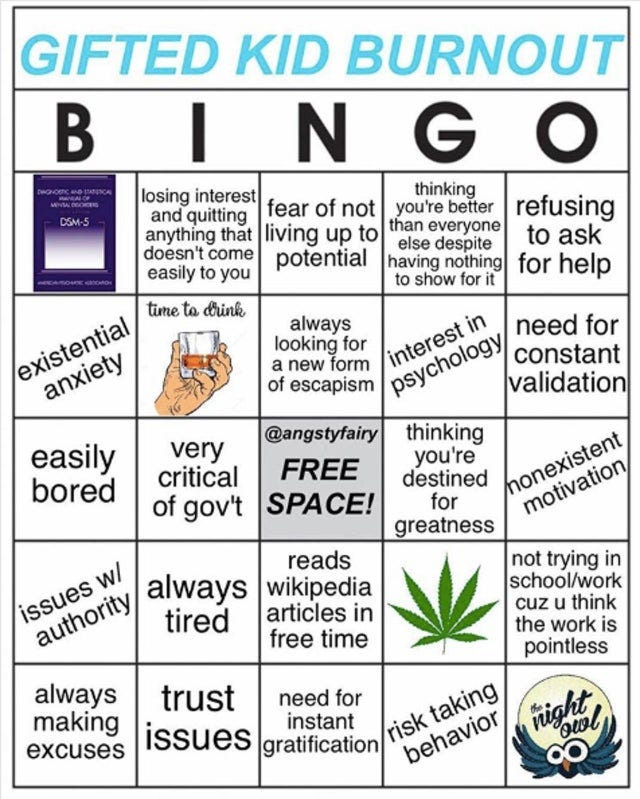

Personal anecdotes aside, a lot of the Internet backlash against “former gifted kids” flared to life in response to this viral tweet.

Some are saying they should “get real problems”, others are expressing how irritating it is to be subjected to the onslaught of grievances these now-adults cite, and this one Twitter user makes a point more cogent than I’ll ever be able to articulate within this very long essay.

Essentially, the idea here is that there is a wealth of millennials (and to some extent, centennials who are just now entering college) who were told that they possessed a rare and magical kind of intelligence that couldn’t be adequately nurtured within the confines of ordinary K-12 classes — they needed to be challenged by a more rigorous form of education in order to blossom into the geniuses they always were. Yet once these students escaped the comfort of adolescence and were subsequently thrust into the cold and severe Real World, they were forced to grapple with the fact that they weren’t the best anymore. It’s a depressing tale, to be sure.

(Side note: if you are someone who’s ever called yourself a gifted kid and/or made sardonic jokes about it, that’s totally fine and understandable. While the Internet discourse around this topic has brought up tons of valid points, I think it’s also excessively harsh and unkind — I’m talking about this because I find the phenomenon uniquely fascinating, not to make people feel shitty or invalidated. Of course, I’m also persuading people to move away from using labels like this, but there’s no shame in falling prey to adopting common online phrases as identifiers — most of the time, we’re just in dire need of a community with the capacity to understand us!)

My primary gripe with the “gifted kid” label is that it’s inherently exclusionary. It feels like a tongue-in-cheek, self-aware, socially acceptable way to assert yourself as the smartest person in a school you attended like, twelve years ago. Moreover, passion for academia and a fixation with schoolwork aren’t exclusive to those deemed “gifted”. Many students are exhilarated at the prospect of learning but are not afforded an appropriate level of care or the ability to express their desire — whether that means they lacked the privilege of having enough free time to study or complete assignments or that their neurodivergence was never acknowledged and accommodated for in the classroom. Additionally, it’s been well-documented that structural racism plays a role in inhibiting students of color (particularly Black students) from achieving their full academic potential since (among a slew of other systemic factors), they receive limited access to honors and advanced-placement courses and experience disciplinary measures at disproportionate rates when compared to nonblack students.

Simply put, our educational system is deeply flawed; as such, it isn’t particularly constructive to use markers like high grades, exorbitant participation in extracurriculars, or placement in programs like GATE (Gifted and Talented Education) as proof of anyone’s intellectual aptitude. When you inflate your own sense of self via these attributes, you aren’t doing anything tangible except perhaps unintentionally creating an Other. Ascribing value to the virtually meaningless “gifted kid” title is a way of assuaging our fragile identities — it is proof that our suffering has merit. You might be flailing around helplessly during a post-grad existential crisis with no clue about how to survive past high school, but at least you were good at something back then!

Adulthood is harrowing. Not only is no one prepared for it, but also it’s kind of earth-shattering to realize that the people you’ve trusted your whole life don’t really know what they’re doing either. That’s why we’re seeing so much language that aims to convince young adults that we don’t have to deal with all the pressures of growing up, or at least not yet! It’s really nothing new; millennials had their cutesy “adulting is hard” memes, and now Generation Z has ironic tweets about how we’re all just “twenty-something teenagers”.3

Among the devastating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic is the pervasive feeling that we’re all mentally “stuck” (i.e. emotionally stunted) at the age we were when global lockdowns first commenced…so of course none of us feel equipped to re-enter society and adapt to the myriad of expectations set for us. It’s temporarily soothing to partake in these Internet trends and remind ourselves that everyone else is just as dysfunctional and confused as we are — but this incessant infantilization is a desperate plea to avoid dealing with the reality that we are getting older.

Those who affix their personalities to the title of “former gifted kid” bear parallels to those who relive their high school glory days by eagerly retelling anecdotes of their life as a football star. This is not to say that we shouldn’t have sympathy for these experiences, because we most certainly should! But also, we should recognize that it’s a fundamentally unhealthy way to identify yourself for the rest of time and tends to overshadow the millions of children who have been neglected and failed by the educational system.

We’re all just scared overgrown kids, clinging to evidence that our lives have been somewhat useful in order to soften the inevitable blow of being viewed as mediocre and untalented after leaving the safety of our homes. And it’s not just academic achievement that tethers us to our elementary, middle, and high schools; it’s the ease at which we were able to form genuine human connections, whether with classmates we can now call life-long friends or teachers who often take on the responsibilities of parental figures4. In comparison, adulthood can feel profoundly isolating…it’s no wonder we’re all fighting it so dearly.

Mom, am I still young?

Can I dream for a few months more?-Mitski, Class of 2013

Our collective desire to fetishize and glamorize mental illness in those deemed geniuses has set a disturbing precedent for the way we treat our own psychological afflictions. The truth is, pain doesn’t need to have produced anything in order for it to affect us so brutally. We cannot reach greater depths of intellectualism or soar to higher planes of creativity by plunging ourselves further into pity and despair, by lovingly crooning in our own ears about the importance of preserving damaging self-fulfilling prophecies relating to the plight of our inherently “gifted” natures. All this rhetoric does is actually distance ourselves from the rest of the population which also feels the same kind of seclusion and dissatisfaction with the stress and mundanity of life…it’s reflective of America’s rugged individualist culture that implicitly coaxes us into cementing ourselves as Different, and therefore better than everyone else.

But it’s okay that we’re all the same, and it’s okay that there isn’t anything special about the ways in which we suffer! The seductive “former gifted kid” fantasy might be nothing more than smoke and mirrors, but it should have never determined anyone’s worth or sense of self in the first place. That’s something we need to find for ourselves — and though the process itself might be tiresome and perilous, at least we’ll come out of the other side knowing that our newfound identity is real. That’s all any of us can really ask for.

Once again, thank you so much for reading this post! My brain is buffering too much for a proper outro since I semi-foolishly wrote this all in one sitting, but I’m so excited (and quite nervous) to share this one with you all! I hope I tackled this topic with the empathy it deserves, but there’s so much nuance to it that I can’t wait to read your responses! I’m curious to know if you have different interpretations of the phrase itself or personal experience being in gifted programs or feeling excluded from them (if you’re comfortable sharing, of course). And as always, this is your daily reminder to do something kind for yourself and take a deep breath…I hope you have a lovely rest of your evening!

<3,

sonali

…which was especially crushing as a daughter of Indian immigrants — not that they made me feel shitty in the slightest, but longstanding cultural perceptions of how Asians are supposed to perform academically still weaseled their way into my brain and left me feeling a little guilty.

For what it’s worth, I don’t feel that way anymore and am very grateful about it — there is a whole life ahead of me and I’m just beginning to make something of myself!

Author’s note: I just realized Madison Huizinga made the identical point in her post, “The Twenty-Something Teens”, so please go check it out!

Shoutout to my very cool high school English teacher for reading all my self-indulgent, weepy poetry!

Love, love, love this! Thank you for sharing, and I am sure many of us can relate. Oftentimes we forget how self-deprecation actually can hinder us from growth! Great piece :)

sonali-- what a thought-provoking (and exceptionally timed) piece! i have a ton to say... your writing tends to do that to me :) it helps that i've recently been confronting the roots of a TON of my beliefs centering around academic achievement and success!

as a preface: i take great issue with the separation of children into gifted/non-gifted/average categories!! it suggests that each person learns in the same way, deals with the same circumstances, and comes from the exact same background and privilege. this is simply not the case, but the american academic system operates on the assumption it is. sorting children by capability and "potential" is so dismissive of each person's uniqueness and fails to acknowledge that there is great diversity in learning styles. beyond that, it removes so much value from the act of learning in itself (is that not the whole point of school?), and fixates on statistics-- grades, test stores-- as a marker of someone's abilities and of their desire to learn.

i grew up being placed into gifted/advanced academic programs. i was incessantly told how exceptional i was and how i deserved the entire world and would go very very far because of my intellect, etc: the regular dialogue fed to the kids whose learning styles and proclivities best conform to western academic practices and teaching structures. there was a definitive outgroup created in my elementary school, and hence a power hierarchy: inflated egos and high expectations ran rampant among the "gifted kids." it makes sense that 10 year-olds would cling so strongly to this identity of smartness; it's a formative time in your life! along with the label, i think, comes the development of personal expectations about what you are supposed to achieve. your self-worth becomes deeply integrated with your academic performance; after all, that's what you're told defines you.

i think what makes "gifted kid burnout" feel so painful is that it's a betrayal of the messages you were fed about how things were meant to play out. the gifted child was meant to be perfect, to hit no bumps in the road, to skyrocket to success on a seamless, barrier-less trajectory. it's hard to confront the fact that life isn't perfect, especially when you were conditioned to believe it would be. not only that: that you deserved that perfection because of your exceptional intelligence. to confront difficulty might feel like an existential betrayal of the way you think you're meant to move through the world; it means accepting the fact that progress is nonlinear, and that things, well, don't come easily all the time.

the proliferation of complaint about gifted kid burnout, then, is a collective grasping at a new identifier to replace one which has been lost. it is a hyper-fixation on suffering which feels undeserved because it was so profoundly unexpected. it is an attempt to cling to a collective struggle, to find meaning and to differentiate oneself, when the core of your self-definition was revealed to be false.

your concluding comments on suffering actually remind me a lot of a critical analysis paper i wrote last year, which explored the relationship between suffering and creativity/success, and the pervasive dialogues which tell us that suffering makes our work mean more. i specifically studied the romanticization of the "suffering artist," studying the consequences it had for the treatment of mental illness, and also the stigma tied to it. the trope essentially promotes the idea that suffering is critical to producing meaningful work; this leads people to (in your words, because they fit perfectly) "[plunge themselves] further into pity and despair." it causes mental illness to be viewed as a creative tool, and a mysterious key to unlocking genius. i must say, from personal experience: no!! it does not make you a genius! i can vouch: at my lowest mental points, i feel foggy, out of touch, lost, and unable to focus. my ability to think clearly is overwhelmingly hindered. the glorification of suffering entraps people in states of disarray, which they (and society) falsely regard as the source of their extraneous, unique greatness.

because this is beginning to become an essay in itself i'll stop for now; regardless, thank you for sparking so much reflection for me. and, i might add, in such admirably eloquent language ^-^

hope you are taking good care of yourself and making space for rest as the school year gets into full swing. much love <3